Mood Indigo

After my last visit to Arizona in October of infamous 2020, I felt an unusual sense of accomplishment: my Avalon-blue 1995 Range Rover Classic was complete. There were little things to do and fix here and there, like a better stereo or more-convenient storage, but otherwise I felt like this was the vehicle I could take on a trip to the land's end at any time. Like, call my lovely wife from the office and say "I am going to stop by for dinner, and then drive to Alaska. Wanna join me?"

Cue Forrest Gump: "And just like that, my running days was over."

So was the Classic's running days.

One Saturday morning in November I took Jules for a morning walk on the beach in La Jolla, and upon our return the truck started very reluctantly, and seemed to have only a few ponies left - so taking the highway home was out of question, and I had to use low range to climb from the sea level. The Classic barely made it home, and required nearly a running start to take its spot at the garage apron.

The next morning it would not start at all.

The usual electrical suspects - distributor cap, rotor, ignition wires and spark plugs, this and that sensor - were replaced in a quick succession, to no use. I was not so much furious, but determined to find what happened; after all, what if it happened to me halfway between Dawson City and Fairbanks? Or in Death Valley? With that determination, I refused to take the truck to a competent shop, and tore into it "with a vengence and furious anger." In a few days, I was able to start it - but it ran terribly, and was making sounds like it was about to toss a rod through the block. I shut it off and resigned to get some diagnostic equipment from Amazon.

Then we attempted a family trip to Jackson, Wyoming, in a much-younger Land Rover LR4 with one-third of the mileage of the Classic - to find it dead on the side of the road in Nevada.

Fast forward to mid-January of 2021.

That Classic is stlil sitting on the garage apron, with engine half torn apart and parts everywhere. I figured out what it was - a timing chain slipping a couple of teeth on a worn and defective camshaft sprocket; this is a kind of a failure you don't anticipate when you're going to the land's end. It could have been fixed "in the sticks," but without replacement chain and sprockets the fix would not have lasted very long. I had all the parts and tools, but not a whole lot of motivation to wrap it all up.

Until I receive a message from Chris Snell. He has a bad case of cabin (or island?) fever in the middle of Pennsylvannia, and wants badly to take a trip just about anywhere. I want to drive to Idaho - but it involves a lot of very cold camping nights. Chris wants to drive to Mexico - but what with the pandemic raging on, and border crossings?

There's another issue - which vehicle to take? Besides the immobile Avalon Blue Classic, I have a couple of other Land Rovers of similar vintage, but neither is entirely good for a long single-vehicle trip. After some vascillating between this or that truck and jobs needed to make them trip-worthy, I set again at making the blue truck work. Eventually, it pays off - but barely two or three days before the impending trip. I don't like the idea of a trip in a vehicle immediately after a major repair (especially done by me, and not by a professional), but... here it is.

Chris arrives a day before the trip; we still haven't decided where we're going. By that time, Lena tells me that Jules The Airedale goes on the trip with us - which changes the equation somehow. Baja California is out of question now, and the cold winter weather front passing through Southwest makes a trip through Death Valley less attractive.

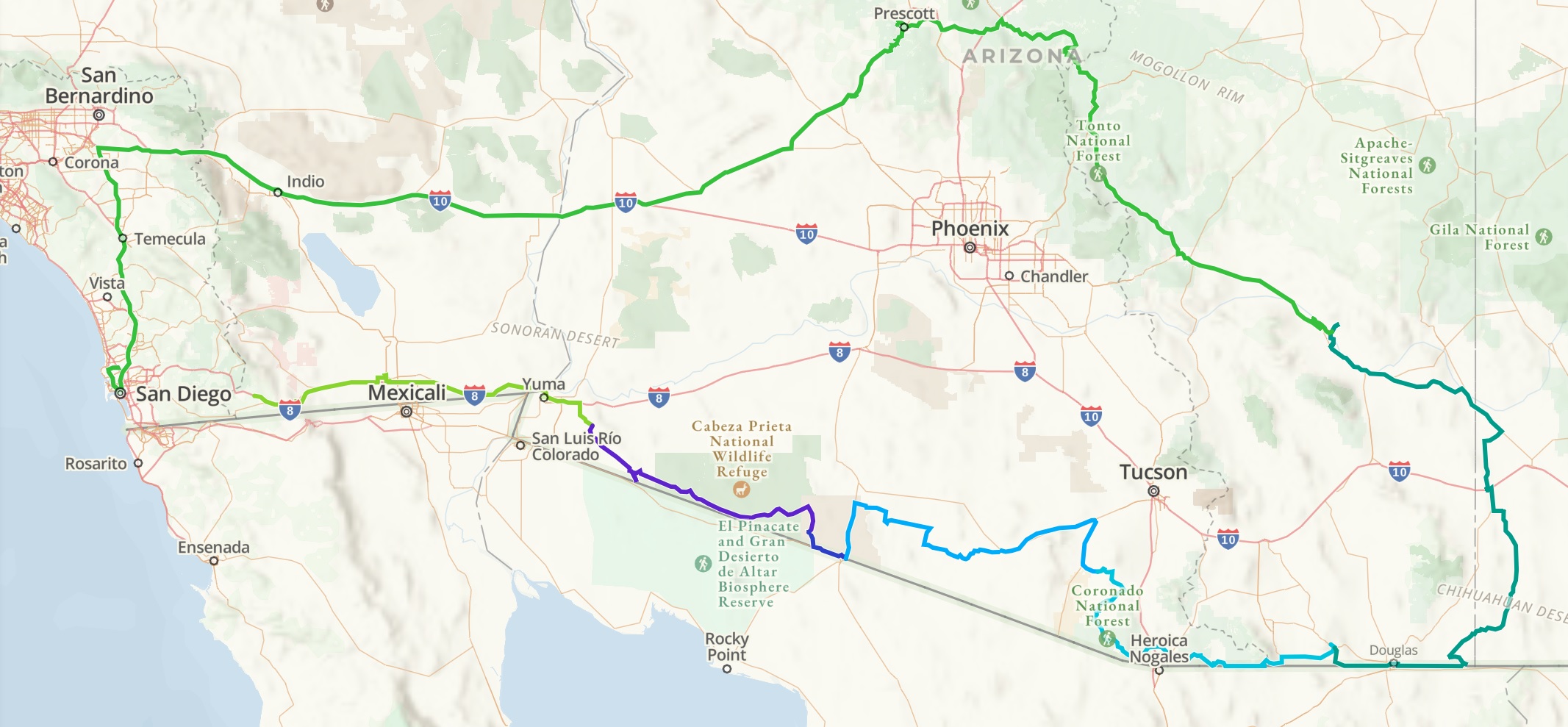

So, on a brisk Saturday morning, out of a choice of going North or South, we're on our way East to El Camino Del Diablo.

El Camino Del Diablo

Let's get Wikipedia ready:

El Camino del Diablo (Spanish, meaning "The Devil's Highway") is a historic 250-mile (400 km) road that currently extends through some of the most remote and arid terrain of the Sonoran Desert in Pima County and Yuma County, Arizona. In use for at least 1,000 years, El Camino del Diablo is believed to have started as a series of footpaths used by desert-dwelling Native Americans. From the 16th to the 19th centuries, the road was used extensively by conquistadores, explorers, missionaries, settlers, miners, and cartographers. Use of the trail declined sharply after the railroad reached Yuma in 1870. In recognition of its historic significance, El Camino del Diablo was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1978. It has also been designated a Bureau of Land Management Back Country Byway.The name, like its other historic name Camino del Muerto <...> refers to the harsh, unforgiving conditions on trail.

<...>

Today, the Camino del Diablo remains a dirt road, suitable for four-wheel drive and high-clearance vehicles carrying extra water and emergency equipment. No emergency or tow services are available, and visitors use the trail at their own risk.

Sure sounds like fun!

On top of its historic significance, the U.S. portion of El Camino Del Diablo passes through and by the Barry M. Goldwater Air Force (bombing) range, where ... well, things get bombed. So all visitors are required to view an instructional video (cheating is discouraged) and obtain a permit online. I spent a few memorable nights on this range about 18 years ago - it was enjoyable to see a Hellfire shooting practice a mile or so away.

Okay, it was not really spur-of-the-moment decision - we discussed it at some length a couple of days before the trip, barely enough to get the permits.

So now we're moving briskly East on Interstate 8. Our first stop is for gas - not sure if it was related to my recent repair, but the Classic is seriously thirsty, to the tune of 10 mpg. The next destination is a Mexican supermarket in El Centro (masa, tortillas, vegetables, cooking oil, and toilet paper), then - a late lunch in Marisco El Azul in Yuma (thank you Jordan Miner for suggesting the place). The octopus ceviche is out of this world.

We find ourselves in the mid-afternoon, still in Yuma. We top off the gas, buy firewood (which would remain on the roof rack until the last night of the trip), and leave the pavement.

The trail soon ceases to be made out of nice soft sand, and becomes rocky. The combination of the road surface and the Sun disk getting past one-palm-width from the horizon makes me suggest Chris that we can, for once, start looking for a suitable campsite before it gets pitch dark.

Our resolve to push forward vanishes soon at a sight of a nice flat site, complete with fire ring and enough room for a truck and two tents.

Chris suggests we gather firewood before doing anything else - so by the time it gets dark(er), the tents are still in the truck but the fire is going. After a late lunch in Yuma, we are still not hungry - so beers and Bourbon along with some snacks do the trick.

We hit the hay pads in our tents late, allowing all side-by-sides from Yuma to return home.

The sleep is fitful, frequently disturbed by the engine sounds carried from both sides of the border.

One of yesterday's discoveries was that we don't have any salt for our food - so the morning begins early with bacon sizzling on the frying pan. I also took along the food that Jules doesn't like - so it becomes a double struggle - Jules' eyes are clearly accusing me of totally lacking conscience (something he definitely does not possess, in my opinion).

By nine in the morning, we run out of things to do at the camp and pack into the Range Rover, and roll out.

Soon we come to our first fork - and ignore the turn-off to Fortuna Mine (remnants of a mine and a ghost town).

The road finally wiggles out of the rocky section crossing the foothills of the Gila mountain range, and we're on soft sand with a trace of washboard. Soon we see one of many technical means employed by the Border Patrol - a pickup truck with a tall mast in the bed, adorned with an electro-optic turret and quite a few antennas. Nobody seems to be around.

Soon, we begin to sense the presence of a bombing range nearby - by the signs warning us of unexploded ordnance and laser in operation. The UXO on the bombing range is comprehensible, what's the deal with the laser? I delve into delicate matters of rangefinders, laser designators, and NOHD (Nominal Ocular Hazard Distance - here's some exciting read.). In case the link goes 404, the military is using short-wavelength infrared (SWIR) rangefinders that, while being invisible for a human eye, can nonetheless damage the eye at distances of many miles to tens of miles.

I vaguely recognize the landscape - we should be getting closer to Yodaville ("population 0, home of Mk 76"). While I am still looking in my desk drawers for an 18-year-old but good in-situ photo of this place, I find that the aerial view is not half-bad on Google Earth.

Yodaville is a mock town built for urban warfare training around 1999, mostly used for bombing practice (as opposed to many sand-colored structures sprouting at Camp Pendleton, California). It is pretty eerie at night, with structures made out of sea containers up to three stories tall, many with jagged holes five feet in diameter. In the past, there were vehicles - from old taxis to tracked personnel carriers - parked on the "streets" of Yodaville, with the same signs of carnage.

From about two miles away, it doesn't look imposing. If you didn't know what it was, you wouldn't even pay any attention.

The road continues along the feet of Tinajas Atlas Mountains. Little by little, the plants of Colorado desert are replaced by those of Sonoran Desert; most notably, the Organ Pipe Cactus plants, rarely seen in the deserts of Colorado and western Arizona, now show up regularly.

Chris' driving concentration is taxed by Jules demanding attention frequently. Jules mostly wants his presence acknowledged, and every now and then he'd like to rest his giant head on someone else's shoulder. Not from the top, but lean into it sideways.

We meet a group of side-by-sides from Yuma, wave, and motor on.

In a little while, we see a mast - with a few antennas, and a couple of boxes on it. We pull over to check it out.

The bottom box of the mast has one control: a red button. Pushing this button is all you have to do when you find yourself in this unforgiving desert without water and means of transportation. Read the inscription in the zoomed-in photo; it applies to a poor soul in search of a better live North of the border and a schmuck with a broken down Land Rover equally.

Not even five minutes later we get our first sight of the largest monument a President of the United States could erect for himself: The Wall.

Facing a fork - the left continuing to El Camino del Diablo, the right going South towards the wall, we take the right.

It takes a while to arrive to the border - about two and a half miles. All this time The Wall keeps growing vertically and laterally, growing from a thin line on the map to a fat undulating line on the horizon to something capable of changing the local climate (at least it seems so, given the abundance of shade it provides mid-day).

Pink Floyd - "Mother," from The Wall

We aren't alone - there's a large group of visitors in side-by-sides, likely retirees from Yuma. We chat a little bit and take a few photos, until a lil'ol'lady stops by and informs me in Aesopian tems that Jules has taken a shit.

People, just to remind - we are in the midst of Sonoran desert. As much as I dislike an idea of a CBP officer to step in the Jules' little pile, there's an equal chance to step in a larger pile of burro or horseshit.

The lil'ol'lady, a proverbial neighborhood minder from a Yuma trailer park, is eager to show me where exactly the poop resides. I bury it with a shovel. If you know me well, and you ever hear me mentioning a retirement in Yuma, whack me in the head with that folding shovel.

On the upside for you, my reader, I am now the only person you know and will ever know who buried dog shit in the desert. Brag about it.

We take a few photos near the fence and get moving again. The road to the East along the fence is closed to traffic; it means we have to go back (the Donald Trump's phrase "You have to go back" sounded in our minds, and not just then) a few miles, and reconnect with the original road.

The trail takes us through a shallow Tinajas Altas Pass - which, at the time, we know nothing about besides the name on the map. So we do it without stopping to walk up to the Tinajas Altas - The High Tanks - themselves. These "tanks" are pretty deep and large cavities on the rock surface in the mountains, capturing whatever little rainfall happens in the area - up to the total of twenty thousand gallons; they have been used as a water source for indigenous people and explorers alike - some of which died trying to reach the tanks or finding them dry and void.

Out of the canyon, we find ourselves on a vast plain facing Cabesa Prieta Wilderness in the East. A bunch of dirt roads spread out every which way, and the ones that should be our way are blocked off and closed for traffic. It is somewhat of a concern - we haven't covered even a half of El Camino Del Diablo's length, yet the gas gauge in the Classic is showing about 12 gallons remaining in the tank. The truck's far thirstier than it used to be. We do have a full 5-gallon jerry can with us, but we can't afford a large mistake in navigation.

We spot a large group of jeepers having lunch in the shade of the mountain; these guys are well-equipped, including good paper maps of Barry Goldwater bombing range, Cabesa Prieta Wilderness, and Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. We figure out which is our way, take a photos of the map, and are given a spare map - just in case. Thank you guys!

Soon, we're on the section of El Camino Del Diablo that has been a cause of much controversy recently - the border wall construction crews widened and graded a long section of the road, and many die-hard off-roaders complained that it destroyed the "soul" of one of the oldest and most-remote trails in the West.

It may be; I am not entirely sure that the soul is not damaged by the sounds of unmuffled two-cycle-engine exhaust from dozens of side-by-sides on the trail. I do appreciate the ability to drive at a reasonable speed in high gear, though, hoping to make it to the next gas pump.

Still on this graded section, we meet with a couple on fat-tire Trek bicycles slogging through sandy patches on the road. We stop to chat and offer them cold beer and as much water as they can take; the gentleman, an ex-Marine, tells us (among other things) that his friends in CBP suggested carrying a weapon in case of an altercation with human or drug smugglers. Something to ponder when we camp out near the border.

We stop to check in at the boundary of Cabesa Prieta Wilderness - according to the jeepers we met, an unannounced visit to the place may bring about a very unhappy park ranger.

About half an hour into Cabesa Prieta, after driving by several well-defined volcanic craters, we come to a well-known site of Tule Well. The original well was likely hand-dug by Mexican gold-seekers on their way to California, sometime in 1860s. Throughout its more than 150-year history, it has been abandoned and restored several times; now it is a fully-functioning well powered by both wind and solar panels, with a storage tank and a spigot outside. The water is reported to be brakish, though, and not quite drinkable. In 1941, the Boy Scouts built a cairn-like monument dedicated to opening of the Wildlife Refuge that still stands. There's also a picnic table close by - convenient to have a couple of beers, or a trailside lunch - and an adobe cabin, with a neat fireplace, camping table, and a shelf, inside. I'd definitely spend a night in the cabin if I happened to be there in time - after thoroughly sweeping it for spiders, scorpions, and rattlesnakes.

We must have spent half an hour at Tule Well; all this time, there was a Border Patrol truck nearby, with the officer behind the wheel and somebody in the back. Hmmm...

On the way, we meet a brand new 4x4 Sprinter van with all the trendy accoutrements. A combination of a burly steel bumper, a winch, and running boards is always amusing, but who are we to judge.

The road continues up through a shallow rocky pass, then descends into what looks like a floodplain (Gaia map even shows something called Las Playas between the road and the border fence). It would be bad news to end up here after a decent rainstorm.

Somewhere along, we pass a sizable Border Patrol camp - with buildings, fuel trucks, generators, whatnot, but in our best OPSEC traditions, no photos or coordinates are collected.

For a road this remote, it surely has plenty of roadside information. We drive by a sign advising us of smuggling and illegal immigrants - the suggestion to dial 9-1-1 is funny, since we haven't seen a spot of mobile coverage since leaving Yuma. But here we are, right at the grand entrance to the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. At least, the yellow marker on the map says so.

Five minutes later, we are again tempted by a suggestion to continue North-East towards Ajo; we decline and make a right turn to Poso Nuevo Road, despite emphatic crossing-out of the road on the map at the intersection. By five o'clock we're close to Poso Nuevo well - which seems to be functioning, fenced around, and adorned with "private property" signs. The area not far from the well appears nearly perfect for camping - flat, wide, with soft ground, and almost void of cholla cactus. We set up camp, and are treated to yet another spectacular Arizona sunset.

The rib-eye comes from the fridge and goes to the grill. In some 20 minutes, it is all charred outside, yet on the raw side inside. Somehow, we are not that hungry; Jules is the one who's ready to consume whatever's left of it, but only gets a few bits and pieces.

Don't know what wood species we gather for firewood - but it is awesome. It burns for a very long time, with an even flame, and very few sparks. We enjoy the beers and the Bourbon.

At the nightfall, we are greeted by a coyote bark and howl - which seems to be a hundred feet away. The hills go alive with other coyotes - and Jules stares into the darkness and barks loudly. We hope the desert canines stay away, and mostly they do.

In the middle of the night Jules wakes up in the tent and barks up a storm. I can't make him stop - but he does on his own, and goes back to sleep.

Tally for the day: 114 miles, all on dirt, total driving time - 7.5 hours.

Jules sleeps in late - he only makes me get out of the tent around 6 in the morning. I take him for a short walk of the neighborhood - and not a minute away from our camp spot the footprints in the sandy wash: fresh but not ours. Feeling a bit like Robinson Crusoe, I guess that must have been the reason for Jules to go off at night.

We make breakfast - bacon and egg-and-leftover-steak tacos, washed down by couple of cups of strong coffee from the Bialetti moka pot.

Jules makes a show of not letting me pack up the tent. Anytime I'd try to pick an object in the tent - his pad, my pad, a sleeping bag - he'd jump in and sit on it. It is amusing but makes the process laborious.

We're on the road by nine - half an hour faster than yesterday.

Before we have a chance to leave the valley, we drive by an observation tower and a CBP truck with two guys inside. Wonder if they saw us all along, and decided to make a quick recon at night?

Not even twenty minutes into the drive, we hit the wall again. North of the border: lightly-used dirt road, a few Border Patrol vehicles perched on the shallow mesa overlooking the fence. South of the border: major Mexican highway #2, with tractor-trailers rumbling in both directions.

This time, the road continues along the border for about 10 miles, and then veers off to eventually lead us to Arizona State Route 85, and South to Lukeville.

The town of Lukeville is named after the World War I fighter pilot Frank Luke, born in Phoenix, Arizona, and an ace credited with 19 kills (numbers vary slightly). His name is also borne by Luke US Air Force base near Phoenix. Wikipedia's entry on Lukeville is short, and lists the year 2000 census figure of 35 souls, 27 of them - of Mexican descent.

The main attractions in Lukeville ("Gringo Pass") are the gas station and the border checkpoint. Everything else is closed, including the former supermarket now housing the U.S. Post Office.

Fuel worries in the past, we're ready to hit the road again. We'd love to take Camino De Dos Republicas - which would take us back to the border - but it is closed; we continue North on SR 85, hoping to find a trail that would take us further East with the least amount of pavement.

In the land of Tohono O'odham (People of the Desert)

A few miles down the road, we find a barely-noticeable turn-off to a dirt road leading to Kuakatch Pass. The road starts off well, and then disappears in the maze of washes and easy to miss turns. We are officially out of the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, but the plants haven't been told so - so they continue to spread, and seem more-numerous and vigorous than on the Monument. High in the skies, two jet figthers play dogfight, keeping us looking up instead of staying on the road.

Eventually, we pass Kuakatch - with a neat small church, a playground, and a few houses in the brush. We pass by a colorful offrenda on the side of the road. Every now and then we see a hand-written road sign, listing settlements not always shown on our topo map. We cross what seems to be a larger road leading South, but run into the road disappearing in the midst of a vast but empty pasture.

After some meandering, we pass the tiny town of Kupk and keep going roughly East-ward - but soon find the faint two-track we're on, and our position mark on the Gaia screen, diverging from most known roads in the area. In one most-bizarre place, we come across a large field strewn with cattle bones - clearly many more than one bovine passed away here. Chris comes up with the most-plausible hypothesis of the cattle felled by a lightning strike during a monsoon storm.

At some point, the road disappears altogether - in the midst of flat sandy plain overgrown with jumping cholla - to the point that we have to roll up the windows so the "little ones" wouldn't fly into the truck. We really shouldn't be here...

... Which is confirmed soon. Aiming towards the distant Kitt Peak, we manage to find our way to the town of Sells, where we are immediately pulled over by the tribal police. A young cop extremely politely tells us that we cannot travel on tribal lands without a permit, runs our paperwork through whatever system he has access to from his vehicle, and hands it back to us without charging with anything. The permit can be obtained in the tribal office for mere $2, he says, but if we plan on camping... Were he us, he wouldn't camp too close to the border. Apparently, the tribal lands transcend the country border, and so are the families. The Wall has not reached here yet, and there's very little in the way of family members carrying all sorts of stuff across the border. Some of them may be just a little too apprehensive of outside observers.

He certainly has a point. During this conversation, his companion maintained about five or six feet of distance from our truck, on the side, with his firearm within an easy reach. We leave the tribal lands, very impressed with the professional quality of local law.

It is already half past four in the afternoon; soon, we have to start looking for a place to camp. We head North on SR 86; Chris is driving, and I am trying to take photos of the main telescope of the Kitt Peak National Observatory.

It gets darker - we pull off into a dirt road which promises eventually take us to a ghost town of Ruby. There are many campsites along the road - but most are either small, or very rocky, or both. A little side trail going downhill towards a sandy wash looks promising; less than a quarter-mile into it, we find our sleeping quarters.

There's a giant, enormous, fire ring - full of old ash, so Chris sets about digging it out. Jules accompanies me in the search of firewood, which we find aplenty. Soon, we have a campfire well matched to the ring, tents set up, and we are ready to enjoy the beautiful evening. More attention is devoted to the second pound-and-a-half-sized ribeye steak, and it comes out close to perfect. The three of us cannot finish it in one sitting, so a good portion is left over for breakfast.

The campsite is more than 6 miles away from the nearest local road, so the night promises to be quiet. There's a faint drone in the sky; Chris looks it up on the open-source alternative to FlightAware, and determines it to be a CBP King Air 350. We look at its mission profile and make educated guesses of the sensor suite it uses.

We turn in late. The air outside cooled off considerably, and must have formed a good inversion layer; a few minutes after tucking myself and Jules in, I hear something that sounds exactly like human footsteps on gravel. Chris immediately asks me if I heard that - affirmative. Jules is quiet, however, so we decide that we must be hearing stuff from far away, and fall asleep.

The night is windy, and our sleep is fitful.

Tally for the day - 180 miles (~100 on dirt), 7 hours of driving time.

Buenos Aires - Patagonia - Coronado

In the morning, all horizontal metal surfaces show frost on them. It takes a while to make coffee, and, just like in Death Valley a couple of years ago, the water freezes in Jules' bowl. He's not thirsty, but determined not to let me to pack up the tent and sleeping stuff.

We have our hearty breakfast and get ready to go. The first sight we come across is the skin of a dead hereford, followed by a healthy cattle family. We're driving by (what I find later was) San Juan ranch, with a water tank and remnants of an Aeromotor windmill well-used for target practice.

We hit pavement at West Arivaca Road about 15 miles later, and join a near convoy of old-timers moving towards the town of Arivaca.

Besides a functioning gas station (even only having 87-grade gasoline), Arivaca has a well-stocked grocery store. We drive away with a full tank of gas and restocked fridge - with frozen meat, beer, milk, and whatnot. Life's looking up.

Another thing Arivaca has is an office full of promise to immigrants, legal or not, and complete with "defund the police" posters on the side. Apparently, the struggle against oppression is real in this town 10 miles North of the border - Wikipedia offers some curious information:

"The town of Arivaca has been called "...an epicenter of efforts in solidarity with migrants and refugees," according to a Crimethinc publication by a former desert aid worker."Look up CrimethInc in Wikipedia, too - it is fascinating. Not the people you want to mess with.

Our current destination is a ghost town of Ruby - the road to which begins right outside downtown Arivaca.

The road to Ruby is very scenic, but the town is not quite - especially when the caretaker is too busy most of the time to charge each visitor fifteen bucks. Not every ghost town in Arizona is Tombstone or Oatman.

Things improve after Arivaca and Ruby.

We're driving in the picturesque hills, full of grand old oak and sycamore trees, little ponds, and whatnot. We stop for a break in one of Arizona's many Sycamore Canyons, let Jules roam and have a beer.

Soon after, we emerge on a plain North of the town of Nogales (Arizona, and Heroica Nogales, Mexico), and the road becomes paved for a short while - just enough to cross Interstate 19 (I have to admit to not knowing there even was an Interstate 19!), top off the fuel, and move on East.

The road slowly bends back towards the border; we pass through some colorful neighborhoods, including a property where it seems like dozens of Volkswagen bugs found their resting place.

As we climb over a shallow mountain pass, we see that the weather is definitely changing - and rapidly. We are treated to some grand views of San Rafael valley below, and occasional bursts of sunshine light up the road in a manner that would make the turn-of-the-19th-century painters giddy with joy.

Once we're at the valley floor, we see that we are boxed in by either rain or snow storms on all sides. It is surprisingly bright and dry where we are, but the storms are close - creating some drama in the landscape.

Then, the clouds roll in - and everything becomes gloomy. Just as it happens, we drive up to the monument - a pretty prominent one, given the remoteness of the place; we have to stop and pay some respect: the monument is to Fray Marcos de Niza.

I have to admit to not knowing the name - if you do, please pardon me for a little diatribe below.

During almost a quarter of a century living in San Diego, I was fascinated by Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo. The guy landed in what we now know as Alta California - on or around Point Loma in San Diego - about fifty years after Columbus made it to the islands of the Caribbean. Given the typical turnaround time of a trans-Atlantic expedition of the time, the discovery and colonization of the present-day Central America happened mind-blowingly quickly.

Yet Fray Marcos de Niza ended up West of the Southern outcroppings of Rocky Mountains three years before Cabrillo navigated along the Alta California.

Remarkably, not much happened in nearly three centuries since this memorable passage; the ranchers gradually inhabited the beautiful valley, and the discovery of copper ore in the mountains nearby brought about some development in the third quarter of the 19th century. The U.S.-Mexican border in this area was surveyed around 1890, and split the small settlement in half - the northern part known formerly as the town of Luttrell was given a Scottish name of Lochiel by Colin Cameron, a descendant of a powerful Clan Cameron of Scotland.

The monument to Marcos de Niza was built in 1939, full four centuries after the crossing.

About five miles to the South of Lochiel there's a small Mexican town, named after a Russian-born soldier of fortune Emilio Kosterlitzky. The area is full of bizarre history!

We slowly roll through the tiny town of Lochiel, Arizona, possessing none of this knowledge. The town looks eerie, gloomy, and deserted, although there are some well-built and lived-in buildings.

After the trip, Chris dug up a webpage in Tuscon Citizen with old photos of Lochiel border crossing - that was single-handedly operated by Helen Mills, a Border and Customs officer, for a decade in 1960s-1970s. I hope they don't mind me poaching a couple of photos.

Outside Lochiel we spook a flock of javelinas - Jules is excited to see the wildlife, and very loud.

The road in San Rafael Valley makes me feel like I am on Ruta 40 in Argentina; when I convey this near-deja-vu feeling to Chris, he mentions that the mountain range we just crossed is called Patagonia Mountains, with a town of Patagonia about 35 miles to the North-west of us. What a world.

And then we see the old border fence, made of crossed I-beams with a horizontal rail welded to them. It looks a bit like World War 2 era "Czech hedgehog" anti-tank barriers, but is definitely not strong enough to prevent a massive tank invasion from the South. Behind that fence, an old cattle fence with a few strands of barbed wire still stands; together, they are rather a marker of a border than any physical deterrent. Whatever the purpose, the new fence would forever ruin this valley; we spend some quality time coming up with medieval means of access control, and hope we can come back before any of them are implemented.

We follow the old border fence for about 15 miles of rolling hills, occasionally checking the spur trails for a good campsite; it is getting late, and the storms really close in. We could camp anywhere, but the combination of weather with proximity of the border and abundance of cow pies doesn't offer many solutions.

Somewhere along this run, we pass Lone Mountain International Airport - it is shown on Gaia Topo Map, but if you try to Google it, you come across sites with notes like "This map shows the historical location of a feature that is no longer visible." The airport is reported to have three runways, but satellite imagery only show one faint strip of cut grass near Lone Mountain Ranch. We want to take a peek at it, but keep running into "private property" signs. Some other day.

We eventually run into the closure of the border road, and have to backtrack several miles to take a two-track North-east towards the mountains. The road enters the Coronado National Memorial - part of National Park system, created to commemorate the overland expedition of Francisco Vázquez de Coronado from 1540 to 1545.

There is some cruel irony in this memorial - the expedition has been ordered by the viceroy of New Spain, Antonio de Mendoza, in order to confirm the discovery of "Seven Cities of Gold," by none other than Fray Marcos de Niza. The Cities of Gold have never been found, which led to disgrace of Marcos de Niza.

By the time we hit the well-maintained National Park road, it is already dark, and the storms closed in. We take a picture of the last rays of setting sun in the West, chat with a bored Border Patrol officer in his truck near Montezuma Pass, and decide to seek cover in a hotel.

The snow catches up with us by the time we're descending from the pass, and follows us all the way to Bisbee.

It takes some perseverance on Chris' side to track down a person in charge of the front desk of Eldorado Suites Hotel and book a beautiful two-bedroom suite on the ground floor. Jules is very tired, and after a brief walk around the block we leave him in the room and go to get a dinner at Santiago's Restaurant. The margaritas arrive heavily tinted by Curacao liqueur (to justify the house name of "Blue Agave Margarita"), but my chicken mole is awesome.

It is freezing outside; we return to our rooms and have one gorgeous night of sleep.

Tally for the day: 160 miles (130 on dirt), 8.5 hours of driving time.

Bisbee

I enjoy a beautiful hot shower and take Jules for a morning walk around old town Bisbee.

The town is one of these places I missed in many crossings of the state of Arizona and many thousands of miles on its roads. All I know in the morning that it is one of the famous copper-mine towns, and it clearly shows - there's a great exhibit of mining equipment in front of Phelps-Dodge General Office building, built in 1896 and housing the headquarters of Phelps Dodge Mining company until 1961.

Let me bust out a quote from Wikipedia again:

Phelps Dodge Corporation was an American mining company founded in 1834 as an import-export firm by Anson Greene Phelps and his two sons-in-law William Earle Dodge, Sr. and Daniel James. The latter two ran Phelps, James & Co., the part of the organization based in Liverpool, England. The import-export firm at first exported United States cotton from the Deep South to England, and imported various metals to the US needed for industrialization. With the expansion of the western frontier in North America, the corporation acquired mines and mining companies, including the Copper Queen Mine in Arizona and the Dawson, New Mexico coal mines. It operated its own mines and acquired railroads to carry its products. By the late 19th century, it was known as a mining company.

On March 19, 2007, it was acquired by Freeport-McMoRan and now operates under the name Freeport-McMoRan Copper & Gold Inc.

A flurry of our visits to Freeport McMoRan facilities happened about a year after acquisition of Phelps Dodge - and a lot of equipment and employees' artifacts still bore the Phelps Dodge insignia. Most mining towns I've visited in Arizona and Colorado (Bagdad, Morenci, Safford - to name a few) have been Phelps Dodge company towns, actually or figuratively. This mining giant definitely played a large - and not always good - role in development of these towns, the state, and the environment. Wikipedia conveys the environmental impact -

As of 2013, the Political Economy Research Institute identified Phelps Dodge as the 41st-largest corporate producer of Air pollution in the United States, with roughly 4.50 million pounds of toxins released annually into the air. Major pollutants included sulfuric acid, chromium compounds, lead compounds, and chlorine.

Whenever you see a sleek Tesla nearby, chances are that the windings of its electric motors are made from Freeport McMoRan / Phelps Dodge - produced copper. Ponder this for a microsecond. Behind every pound of copper there's a plot of land irrigated by sulfuric acid...

We the apologists of the internal combustion engine can shoulder some blame, too. Besides copper, Phelps Dodge was also the largest molybdenum producer in the world, most of which is consumed by automotive industry. Look up the Henderson Mine in Climax, Colorado, if you're curious.

Where was I? Oh, Bisbee. This town certainly has some storied past: yet another quote, only of a Wikipedia page title and statement below:

Bisbee Riot

"Bisbee gunfight" redirects here. For the 1883 event, see Bisbee massacre. For the 1917 event, see Bisbee Deportation."

This morning, though, it is very cold and peaceful. The town hasn't woken up yet, and we share the streets with just a handful of hardy souls living outdoors and a couple of early dog-walkers. The sunlight slowly reaches the stately buildings on the main street - "Tombstone Canyon Road." The walk is enjoyable, and the recurrent thought of this trip - "I have to come back" - is on the surface.

Half an hour later, we're having coffee and pastries outside the Copper Queen Plaza. A couple with a large friendly labradoodle stops by to let their dog meet Jules; they are from Southern Texas, having fled the coop when the cold storm wrecked havoc with Texas electric grid, leaving a huge part of state without power, water, and supplies. Chris' family still lives in San Antonio, so it resonates very strongly.

Then we're done with the coffee and Jules finishes my croissants, and we're ready to roll. We make a stop at a huge mining pit nearby.

The road takes us South, towards the border. We follow The Wall for more than forty miles, only briefly deviating from it in the border town of Douglas.

In a while, the fence starts a crazy uphill climb, and the traffic is forced to deviate North towards Guadalupe Canyon Road. This one, too, is closed to traffic just three miles from Arizona - New Mexico border. We retrace our steps for nearly eight miles until we intercept a flat wide road going North-East towards Coronado National Forest - Geronimo Trail.

Geronimo Trail

The road climbs out of San Bernardino Valley into the foothills of Peloncillo Mountains. We pass by what used to be a well-developed ranch, with an ornate house facing the road. Nobody seems to be around, and the place looks deserted.

Chris tells me that no matter where you enter New Mexico, you notice that the nature completely changes. I am skeptical.

Five or six miles further uphill, we pass by a little stone marker indicating the Arizona-New Mexico border. I stop by, take a photo, look around and don't see any changes in vegetation. We keep trucking on ... until I discover us in a cedar forest, without any of the oaks and sycamores we saw while climbing uphill. Huh...

A little later we pull over by a large monument - with inscription burned into a wooden plaque between two stone columns. The monument is dedicated to the soldiers of the Mormon Battalion - who came through this canyon about 125 years ago. It is worth putting out the text of the inscription on the monument:

"On November 28, 1896 the Mormon Battalion of the U. S. Army West crossed these mountains near this sumit enroute to California during the Mexican War. Co. Cooke had dispatched scouts ahead to find the best route. An Indian guide, Charonneau, while scouting ahead was attacked by three grizzly bears. He killed one bear which provided meat for the troops.

Lt. Stoneman with 21 men could not find a suitable route down the mountain. The began cutting a road but the task was to laborious and the progress to slow. Col. Cooke then ordered the wagons unloaded and the supplies packed on horses and the mules for transport down the mountain. The wagons were lowered down the 40% grade by ropes. One wagon crashed to the canyon bottom. Henry Bigler wrote, "no other man but Cooke would attempt to cross wagons at such a place. Cooke had the spirit of a Bonaparte".

Wow.

Another mile or two later, we find a secluded spot near the creek, and stop for a little break in the woods. Jules is happy to be in the forest, and explores the neighborhood.

Five miles North-East from this spot, a little less than 135 years ago, a group of 39 Apache warriors led by one named Geronimo gave up trying to outfight and outrun a nearly 5,000-men-strong force of General Nelson Miles. Geronimo was officially the last Native American fighter to surrender to the United States of America.

Of course, I learn all of this way after the trip.

We finish our beers and move on - to the grassy plains of New Mexico, with Animas Mountains looming in the distance.

The road descends into the plains, and we find nothing to rest the eyes on for a long while. We pass through a little town of Animas; the gas gauge is inching lower, and I suggest we look for a gas station soon. The plan for the day includes crossing Interstate 10, and we are certain to find one at the intersection with Highway 80.

There's no gas station at this junction, should you ever plan to visit these places.

We pull into the Interstate, and reach normal highway speeds just short of an exit to the ghost town of Steins. The town is closed to visitors - all of it, including a wooden outhouse.

We continue North on dirt, aiming to eventually get to the U.S.70, and reach it in about 25 miles. Soon, we are back into the Grand Canyon State.

Then, the sixty miles to Safford (give or take a few) pass in frequent watching of the gas gauge. I successfully predict hitting the gas station after the "low fuel" light illuminates, and we happily down about 22 gallons of premium into the tank.

It is already late, and we need to find a place to camp quickly. Mount Graham looms over the area, but it looks like the good camping locations are snowed in. Chris steers me through a maze of dirt roads going around private ranches near Thatcher, Arizona, and into the foothills of Gila Mountains.

We realize that we're driving through an ancient volcanic tableland, and can't find a single suitable place to camp - everything is rock-strewn or overgrown with cholla. We remember that we've passed by some planned, started, but never built neighborhood - so we turn back and find a great house site with a smooth concrete slab and a promising fire ring.

The road must be going to some distant ranch - as we are setting up the tents, a pickup truck with two gauchos in sombreros bounces by. The guys seem to be friendly.

When the night falls, Jules peers into darkness and barks furiously. We don't know what it is, and walk a few hundred feet along with Jules to investigate - nothing is out of ordinary.

It is our last camping night - so we finally make use of two bundles of firewood we've lugged around for nearly a thousand miles. Along with local dry wood, it makes some heat - but it gets cold quickly. Chris is happy to demonstrate his Arctic-grade Carhartt pants; we down our last remaning beers, and cook the flank steak procured in Arivaca two days earlier.

You can always count on Chris to dig up some remarkable information - this time, it is about the observatory visible near the top of Mount Graham. The dome we see apparently houses Vatican Advanced Technology Telescope; looks like Holy See started its investment in astronomy about 440 years ago with the Gregorian Tower in Vatican, and has never stopped since. Astronomy is some fascinating stuff, isn't it?

Jules really, really wants me in the tent - he stands in front of it shivering from cold. We eventually break up the conversation and retire for the night.

"And just like that..." as I just managed to tuck Jules and myself into something warm, we hear a very distinctive "pow" of a shotgun in a distance. Jules is out of his warm wrappers and barks up a storm; the shotgun reports continue, and we ponder our options for a while, until we decide that we don't have the firepower to offer any resistance, and fall asleep.

The night is bitterly, ridiculously, cold.

Tally for the day - 266 miles (140 - on dirt), 8 hours of driving time.

Home run

The sun is up, and so is Jules. I took care to keep him under covers during the night, so he's well rested. Too bad he doesn't drive...

We get out of the tent, I pour water in Jules' bowl and go back to rekindle the campfire. By the time the fire is going, Jules' water freezes, and he's not interested in chunky ice.

The stuff goes back in the truck without any regard for ease of retrieval: it is our last day. Jules does his thing with not letting me roll up the pads, sleeping bag, and the tent, and it is not that funny anymore.

It takes a while to find our way back to U.S.70 - most dirt roads shown on Gaia Topo maps are on private ranch lands, and posted very clearly. We cross Gila River on an officially closed-for-traffic bridge, and finally leave the dirt in Fort Thomas, Arizona (nothing is open).

For about an hour, we drive through Apache lands; looks like the pandemic hit the local population pretty hard - enough to put up huge signs warning passers-by to stay off the local streets, and guard booths to keep the riff-raff out.

About 8 miles before the town of Globe, we pass San Carlos Apache Airport - with a couple of decaying DC-3s in the field, and a rare sight of a Grumman Albatross missing an engine.

Soon, we're in Globe, Arizona, and it feels homely enough to get a cup of coffee and take a stroll.

An antique store on the main drag in Globe has a seven-cylinder radial aircraft engine on display - makes me wonder if it came off that Albatross in San Carlos.

As we drive through the town, we see an unmistakable sign of an open-pit copper mine. It is Old Dominion Copper Mine, established in 1880 and purchased by (of course) Phelps Dodge in 1904. It remained in operation until 1931, with its share of labor unrest, yet supported the town for a good half a century.

Our intense dislike for large metropolitan areas makes us consider the route: South-west on U.S. 60 towards Interstate 8 would be prudent, but... we choose North towards Tonto National Forest. Chris is driving, and I am enjoying the views of Theodore Roosevelt Lake.

Our progress is moderate - we pass the towns of Roosevelt, Rye, Payson, Pine, and Strawberry; the weather is spectacular, and we are treated to views of wildlife yet another old car rally.

The roads climb higher and gain about five thousand feet in elevation, so the scenery changes from Sonoran desert landscape near Roosevelt Lake to a healthy pine forest, with ground nearly completely covered with snow from the last storm. We have to stop and let Jules play.

Our trip - quite literally - is all downhill from here. We try our best to stay on higher ground as long as we can - by driving through Prescott, deciding on a place for Chris to live in Prescott, and having a great late lunch (or an early dinner) at Farm Provisions. Now's time to go home; it only 450 miles away, give or take a few. My camera also runs out of room for photos - for the first time in many years - but it is perfectly okay since it is my turn behind the wheel.

We don't have too much entertainment on our way South-west on routes 89, 71, and 60.

Maybe, with the exception of miles and miles of white-painted steel fence lining the highway around Yarnell, Arizona. Once you realize just how long ago that fence showed up for the first time, you wonder about its cost - and the wealth of the owners of that fenced-over land. In case you are curious, we are talking about Maughan Ranch - encompassing more than half a million acres in the middle of the state. Read up on Rex Maughan's life story - it is fascinating, in the "American Dream" sense.

As for many other things related to this trip, there is an unexpected brush with the past for me: the Robert Louis Stephenson estate in Western Samoa, which I visited about two decades ago, is preserved and turned into a museum with a direct effort of Rex Maughan. Seems like a lot of things in this world are interconnected.

To keep me awake, Chris plays a lot of music from his vast collection; the most-memorable and rather fitting was "Allá en el Rancho Grande" from 1920s. The version he plays is a famous one - by Roger Creager and his father. I have to learn to play and sing it - critics be damned.

There is a good article about the history of this song on a UCLA Library website, a worthy read.

We're in San Diego just a hair after midnight, after many a fuel stop. Jules throws a fit when I try to help Chris to unload his stuff from the truck at the hotel - this dog really makes every enclosure his home, and tries to keep stuff where it belongs - but warms up to the idea of going home.

It takes Jules several days to catch up on his sleep.

Tally for the day: 693 miles, 13 hours of driving time.

What shall we use

To fill the empty spaces

Where we used to talk?

How shall I fill

The final places?

How should I complete the wall"

Pink Floyd - "Empty Spaces," from The Wall