San Diego - Glamis - Quartzsite - Yarnell - Prescott

September is a perfect time to enjoy a brief fall season in the mountains of South-Western Colorado.

But any way from San Diego to San Juan Mountains starts with the desert: this time, we cross Imperial sand dunes in old Colorado River floodplain.

Pandemic or not, but the goods from China must make their way East from the Port of Los Angeles. Right after the railroad crossing, highway 78 winds its way along Chocolate Mountains.

We part with California in Blythe, and with Interstate 10 - 35 miles later. Our travels continue on the U.S.60, AZ SR 71 and 89 towards Prescott. The town of Yarnell nicely breaks up the scenery of abandoned trailer parks on the side of the road.

A promenade on a dirt road off Highway 89 ends quickly at a trash pile; one object stands out from broken furniture and construction waste.

In the morning in Prescott, I look at the photos and wonder how come I missed Whiskey Row and Apache Lodge? Need to pay more attention to local charm!

The adobe-house-look of Apache Lodge may appear fake - however, it is a relic from 1940s, and the first Motor Inn in Prescott.

Prescott - Jerome - Schnebly Hill - Navajo Lands - Durango

On a sunny morning, the old mining town of Jerome shines.

We pass Sedona without slowing down even for a cup of coffee. Our next destination of sorts - Schnebly Hill road.

The Schnebly Hill road starts off nicely as a city street, but loses pavement and turns pretty rough quickly. As we get closer to the top of the [Schnebly] hill, the views change from good to great to magnificent.

Schnebly Hill road ends at Interstate 17, which we take North to Flagstaff, and on towards Navajo lands. We forgo the detour to Monument valley, and keep on trucking along the U.S.160 through Tuba City, Kayenta, Four Corners, and Cortez, without much of a pause.

Last few years wore heavily into the local life - Kayenta coal mine and terminal closed along with the Navajo electric plant near Page, once vibrant Anasazi Inn stands empty and looted (actually, both Anasazi Inns - one on U.S.89 near Cameron, another - on U.S.160 near Kayenta), a roadside stop and gas station at Dennehotso are closed.

Many now-defunct service stations have been adorned with very colorful art, and stand out oddly in the middle of empty parking lots gradually taken over by the weeds.

We get a glimpse of snow-covered peaks of San Juan Mountains only in Mancos, halfway between Cortez and Durango.

It is already pitch-dark when we knock on the door of Seasons of Durango in hopes of a dinner. The restaurant does not disappoint - the food and drinks are great.

Durango - Bolam Pass - Ophir Pass - Ironton - Ouray

Downtown Durango is quiet and peaceful during our morning walk with Jules the Airedale.

We have our breakfast on Main Avenue, and head out North towards Ouray. There's a twist, however - we plan to leave U.S.550 at the Purgatory, and follow the dirt across Bolam Pass all the way to CO SR 145.

The road passes through aspen groves, past the slopes of the Purgatory ski resort, on and up to higher elevations. We drive by a cabin that is the only reminder of vanadium mining up to 1940s, replaced by uranium mining that lasted for nearly 20 years.

We are quickly reminded that it's been just a few days after the first snowstorm of the season - we stop by a small lake not far from the pass, and Jules enjoys the water in both liquid and solid phases.

We descend to Colorado Highway 145 and turn North. Lena's hopes for a lunch and shopping in Telluride are dashed when we leave pavement yet again, this time in a tiny town of Ophir with its quaint Post Office and strict traffic speed policy - to take Ophir Pass road all the way back to U.S.550.

On the way down from Ophir Pass we are greeted by a large group driving old Ford Broncos - from the early 1966 to the last of 1996.

We don't spend much time on pavement again - this time, for a detour to the ghost mining town of Ironton. Four years ago, we had an incredible success with wild mushroom hunting in aspen groves near the town site; this time we come up empty-handed. Time to hit the road again, so we can roll into Ouray before dark.

Ouray seems to have not a single vacancy in its many hotels and motels, and every bar and restaurant is booked solid. Due to some capricious twist of

coronavirus quarantine restrictions, schools in many towns and states are still closed, yet watering holes already open. We are super-lucky to get seated

as a family at the bar counter at Brickhouse restaurant - and enjoying our food and drinks. In the following few days, we will not be able to replicate this success.

Corkscrew Gulch, Hurricane Pass, California Pass, Animas Forks, Silverton

We settle on one of the least-ambitious four-wheeling plans for the day: take Corkscrew Gulch up to our favorite R&R spot, then on to Hurricane and California Passes, down to Animas Forks, and on to Silverton.

Lena likes Corkscrew Gulch - it is cork-screwy, but not at all rocky. Soon, we are on a little road dead-ending in a gulch near Red Mountain No.1. Jules immediately ruins the mirror surface of a little lake and continues to enjoy life in the fullest.

We break out cold cuts and make Irish Coffee (does Bourbon count?).

On the way towards Hurricane Pass we spot a marmot somehow interested in 4x4s - he seemed to be mesmerized by a blue Jeep.

By the time we can see Lake Como below the road connecting Hurricane and California Passes, we're surrounded by fresh snow.

It gets warmer by the time we reach the ghost town of Animas Forks - town at an altitude of 11,200 ft (near 3400 m) above sea level, that lived for 47 years starting in 1873,

counted once nearly 500 inhabitants reading Animas Forks Pioneer, and buried under 25 feet of snow in winter of 1884.

I do my best not to take any more photos of the Walsh House. Okay, no more than two.

This yellow-bellied marmot was the king of the place. Nice and plump and completely unbothered by our presence.

For us, the road leads downhill towards Eureka and Silverton. We pass by some mine works - separated from the road by a broken-down bridge - and increasingly-golden groves of aspen trees.

Somehow, the best and brightest fall colors are right off U.S.550, between Silverton and Ironton. As the elevation lowers from 11 thousand feet at Red Mountain Pass towards Ouray, fall colors disappear; but now it is the most-entertaining part of the Million-Dollar Highway.

As a bit of trivia - each mile of the 25-mile stretch of blacktop between Silverton and Ouray took a million of 1934 dollars to build. Originally, it had a sturdy fence to keep wayward motorists from plunging several hundred feet into Animas River, but eventually it was taken down to make snow removal easier.

That's a perfect road not to drive drunk.

* * *

The Black Canyon of the Gunnison.

I am not sure how many times we have driven on the U.S. 50 by the turn-off to Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park without even slowing down. Finally, the desire to see the place matched Lena's dislike for off-pavement escapades, and the trip was on.

It is barely an hour and a half-long drive from Ouray; we had no knowledge and no expectations when we turned off to East Portal Road.

The road starts pretty steep downhill, and it gets progressively steeper. Even the first gear in high range would not keep the Land Rover from accelerating briskly, so we resort to second-low.

Besides the 16% grade, the road rivals its Waimea Canyon counterpart in Kauai by the number and radius of its switchbacks; vehicles longer than 22 feet are prohibited on East Portal Road.

If you think 22 feet is a lot for a vehicle - a long-bed GMC Sierra quad-cab is already past that limit, without a trailer! A Mercedes-Benz Sprinter van, the new favorite of RV crowd, hits the limit in the middle of wheelbase options.

It is not like a ranger would walk around your truck with a measuring tape - but you may be way uncomfortable. Speaking of the Sprinter - not even halfway downhill we met a family in one camped at a viewpoint, waiting for the brakes to cool off.

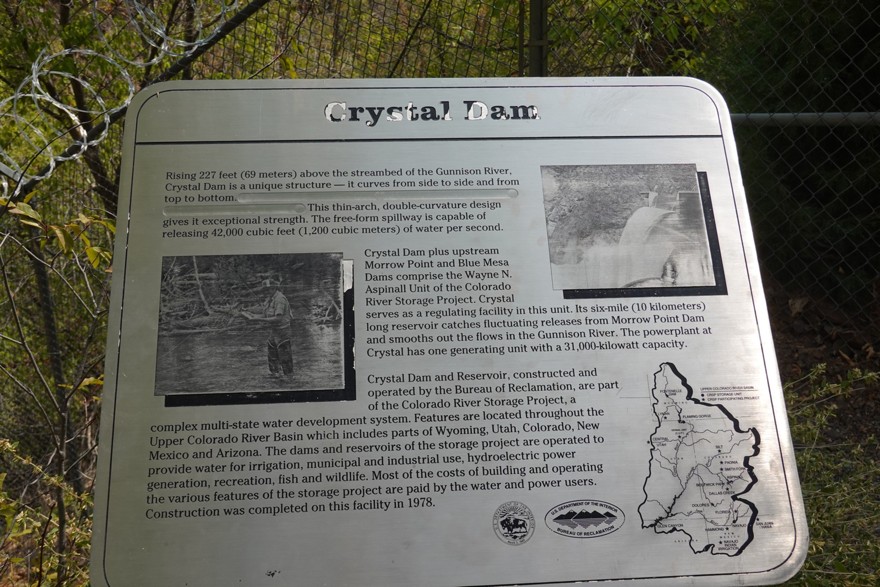

When we arrive to the parking area by Gunnison River, there is not another car in sight. The sheer dark granite cliffs rise almost right from the water; we look at a small dam and a building next to it, and stop to read the information poster.

As it turns out, we are next to an engineering marvel.

Back in 1890s, people in farming areas of Uncompaghre Valley were getting desperate for water - and decided that the Gunnison River is its best source.

A decision was made to build a tunnel under a granite canyon wall, and they set about it. The land survey suggested the start and end points of the tunnel, and the route was sketched.

The task was monumental, and had to wait until Theodore Roosevelt's administration approved the National Reclamation Act of 1902, co-sponsored by the Congressman from nearby Montrose, John Bell.

The bill included construction of the Gunnison Tunnel, and in 1905 the works began - with construction of the East Portal Road. Back in the day, the grades reached a whopping 32%.

A small town was quickly built to house about 250 workers involved in the tunnel construction. The tunnel - 11 feet high by 12 feet across, and SIX miles long, was completed four years later.

Now, a small dam, a quaint building, and a campground, are all that's left from this monumental enterprize.

This National Parks Service webpage has the fascinating details of the Gunnison Tunnel history.

The Gunnison Tunnel is not the only hydro-technical marvel here - East Portal Road ends at the foot of the 323-foot (98 meter) high Crystal Dam, built in 1976 to house a 28-megawatt hydroelectric plant.

The waters of the river are cold and swift, with steep drop-offs - so we watch Jules trying to get a drink but bailing out on the idea.

We head back uphill, and explore the long winding road tracing the edge of the canyon.

The proportions of the canyon can only be appreciated from the top. It is insanely deep - about 2700 ft in its deepest place; and insanely narrow - about 850 feet in its narrowest point (loosely measured in Google Earth).

In the narrowest location, it is twice deep as it is wide, making the side slopes average 76 degrees of angle. The canyon narrows down to 40 feet at the bottom (in the narrowest place).

The waters of Gunnison River stream down a slope that is four times steeper than the bottom of the Grand Canyon - making the stream a Class 5 rapids, suitable only for the most-experienced whitewater riders.

The metamorphic rock forming the canyon walls is not really black in color, but Black fits as a name - some parts of the gorge only get 33 minutes of sunlight a day.

A Wikipedia article about the Black Canyon quotes the impressions of Rudyard Kipling who undertook a train ride (yes, there once was a railroad through this canyon):

"We entered a gorge, remote from the sun, where the rocks were two thousand feet sheer, and where a rock splintered river roared and howled ten feet below a track which seemed to have been built on the simple principle of dropping miscellaneous dirt into the river and pinning a few rails a-top. There was a glory and a wonder and a mystery about the mad ride..."

By the time we reach the end of the road, we feel drained and overwhelmed. We return to Montrose and head back to have a lunch in Ridgway.

The evening sucks. Every restaurant in town is booked pretty much down to its closing time. We find one that isn't, and the "speedy" service and food quickly explain why.

We find solace in the hot springs right in our motel and expire for the night.

* * *

In the morning, I hop in the Land Rover and hurry up from Ouray to Ridgway.

I forgo the morning coffee, and take only passing interest in a beautiful balloon launched in Ridgway: I am waiting to see

The Oxford.

Once upon a time (in 1955), in England, six students decided to do a very British thing - travel the world. Maybe not the entire world, but close to a half of it.

Lacking conveniences like travel planner websites, they settled on two Land Rover station wagons (three-door, 86-inch wheelbase, 2-liter four-cylinder, four-speed manual transmission)

and an overland route from London to Singapore. Being somewhat savvy, they promised to document their route and enlisted a young BBC producer David Attenborough to help with the

filming of the enterprise. Land Rover provided the vehicles; hailing from two famous institutions of higher learning, the students named their wagons "Oxford" (the one with the

license plate SNX891) and "Cambridge" (SNX761).

Their trip took six and a half months, during which they covered about 18 thousand miles. Books have been written about this project - dubbed "First Overland" - and films made.

After the expedition, the trucks were returned to Land Rover, which used them as promotional vehicles until the newer model was released. The "Cambridge" was reported to have met

its demise in Iran, while "Oxford" made it to Ascension Island in South Altlantic Ocean on loan to the British Ornithologists' Union, where it was driven until 1990s.

I am not sure who was the person who found "Oxford" on the island - maybe it was Adam Bennett, a Yorkshireman, who brought it back to the U.K. in 2017 and restored to working condition -

taking great care to preserve its heritage and appearance. He was visited by remaining participants of the original expedition, who took turns driving the little truck.

In 2019, Adam Bennett was found driving and shot-gunning the Oxford along the new route - from Singapore to London. This time, the route took Oxford to the North

of the Himalayas; the trip was well-documented and publicized as the "Last Overland."

In 2020, SNX891 was shipped off to North America, and Rover Owners Association of Virginia undertook a coast-to-coast trip to Oregon, and back.

By a sheer luck, our paths crossed in Ouray, Colorado, and we spent a day four-wheeling with Oxford and a diverse group of people and vehicles.

Our meeting at the gas station in Ridgway:

The group of a Series I (Oxford), Series 2A 88-inch, North-American-Spec Defender 110, two LR4s, and a brand new NAS Defender 110, takes off towards

Ouray and on - to Yankee Girl Mine.

Our progress is slow enough for me to make a quick hop to the motel in Ouray and pick up my ladies and Jules.

The Million Dollar Highway is busy with traffic: one lane between Ouray and turn-off to Mineral Creek is crumbling into the abyss and needs to be repaired.

The traffic is now is using one lane alternating between different directions; it is one reason for a long delay. Another... The little four-banger in the SNX891

was rated 53 horsepower brand new at sea level (about 40 at 10kft), and is struggling to keep the uphill speed between Ouray and Red Mountain Pass -

where the road gains three thousand feet in elevation in about 12 miles. Our little convoy pulls over whenever possible, but that does not spare us honks and

a birdie from an impatient Toyota driver.

A little after Ironton we pull left onto the County Road 31, passing by the remnants of the Yankee Girl Mine - which started its life in 1881 until prospectors gave

up in 1914, and produced over 8 million dollars' worth of silver, copper, and gold ore. Below are the photo of Oxford parked near one of the mine

buildings, and a 1890 photo of the same building taken from the other side (shamelessly poached from Legends of America website).

The place is so scenic that we have to disembark at take a million photos.

We continue on the road, gradually coming down towards U.S.550. All along the road, we spot old mining building and old - and sometimes new! - mining equipment. The place still has plenty of goods under the surface!

Soon, we're at the Red Mountain Pass on U.S.550, just a little over 11 thousand feet. Time to take vanity photos next to the Oxford; we are guilty of taking a few as well.

We leave pavement in a few hundred feet - to the County road 825, bypassing Million Dollar higway in the foothills of McMillan and Ohio Mountains.

The road climbs quickly, and we find ourselves in alpine tundra at the altitude over 12 thousand feet. The views are fantastic, and we stop for lunch. One of the ROAV guys who

also has a second home near Ridgway gives us a visual tour of the roads, lakes, and other attractions visible from our promontory.

Our next destination - Ophir Pass, due directly West from our lunch spot.

We need to lose more than two thousand vertical feet to cross the U.S.550, and then gain another thousand to get to the Pass.

It is hard work and a few gray hairs in a 65-year-old little truck with a crash box and without brake or steering assist.

|

|

|

|

The Western grade of Ophir Pass road is cut tightly into a talus slope of the Lookout Peak.

There are very few spots where two vehicles can fit side by side, so the classic Defender 110 drives off, to keep potential uphill traffic at bay.

We have to wait for a few vehicles to climb before Oxford can proceed; from our vantage point a little under the pass, any vehicle looks like a barely-moving speck on that slope.

We emerge on Colorado SR 145, and drive North towards Telluride - where we break off from the posse, to have a meal and do a little shopping.

I only get to see the Oxford next morning in Ridgway - they take off on their journey Eastward, and we are going to Clear Lake today.

Here you can see more photos of SNX891 (Oxford) in Ouray.

* * *

Clear Lake

The road to Clear Lake starts on the Western side of U.S.550, about 21 miles North of Ouray. It climbs gently at first, through groves of increasingly bright-yellow aspens,

and then picks up the pace through the band of conifer forest, to emerge in tight switchbacks in alpine tundra.

We gain about 2300 feet in elevation in the last 4 miles; whenever we can see the road we just drove on, it looks straight down.

We are by far not alone at the lake - a classical tarn - but manage to snag a great place to park. Jules is cut free, and I break out the field kitchen.

On the lunch menu: rib-eye steak, cheese, and whiskey. It is chilly outside; we chat with a friendly group of Texans, share a few drinks, make ourselves a stiff espresso, and head back to Ouray.

We take our time driving back to Ouray - today it is our last evening here. It is always sad to leave this place.

We are helped a little bit by being unable to find a place to have dinner, and overcharged greatly by the hotel. Oh well...

* * *

Bright and early, we are on the road again - nothing fancy planned on the way back, just put the hammer down and cover these nine hundred miles pronto.

The aspens near Million Dollar Highway definitely brightened up during our stay. After a while, Lena becomes overly concerned with me

taking photos in motion, so we have to pull over here and there and take photos.

Fall Colors

I may have used this before - but... these colors sneak upon you and just smack you in the face.

Just like that.

And they never quite let go, for a good part of fifty miles of the U.S.550.

Near Durango, we are - once again - reminded that the snow is coming (it's already snowed heavily a little more than a week ago).

We retrace our steps through Navajo lands along the U.S.160 and 89, and crash for the night in Days Inn in Flagstaff, right on Historic Route 66.

I guess we bought into this motel as owned by Wyndham (as if it lends any credibility); the lobby is glamorous, check-in

quick and painless. I grab the keys and decide to check the room before we lug in our stuff.

The shock of seeing a barely-spruced-up room with a heavy tobacco smell was unexpected. I would rather keep driving for seven hours

to San Diego than stay in this room; I head back to the lobby and am given a different room. It is indeed a lot better, but now I

can't stop noticing the chairs without any padding, water fauced knobs falling off, painted-over roof water leaks in the bathroom.

The room is livable, however, so we bring over the luggage and drive a mile to downtown Flagstaff for a dinner.

Just like in Ouray - all good restaurants are either shut down due to the pandemic or booked solid. With Jules at hand, we grab

whatever outdoor seating we can, and explore a semblance of Native American cuisine.

Oh yes... people in Flagstaff are weird. Like, on the scale from downtown Portland to Breaking-Bad-weird.

Late at night, we learn that the hotel is also within a quarter mile from a very busy railroad. The trains rumble through what seems like

every 10-15 minutes, and announce their passing with bells and horns at major road crossings.

In the morning, we have a short breakfast in what must have been a gorgeous reception area, and wonder - when was this motel built and

who owned it before Days Inn and Wyndham ran it down? Not too many motels these days have delicate scale railroads built in the planters (broken),

and pool and ping pong tables and a piano in the recreation area.

We fuel up right before hitting the Interstate 17, and keep the hammer down for a good part of our road to Yuma. It is so hot outside

that Jules would not even set his paws outside of the shade of the gas station in Dateland, Arizona. Lena grabs the helm and I am left to

take photos of sand dunes and the desert.

The last honorable mention of the trip - the Desert View Tower, briefly visible from Interstate 8 and captured on the last photo.

Built in 1922 by Bert Vaughn, a real estate developer from San Diego, who also owned the nearby little town of Jacumba. Now on National

Register of Historic Places, it houses a museum, a gift shop, a garden of stone sculptures by Merle Ratcliff, and it is a

great place to stop and break the monotony of Interstate highway travel.

Oh yes, and it is currently closed - hopefully, not forever.

* * *